003 — Wordsmoke

A student’s map of Oxford, the trauma of Finals and a fun game to play with license plates

Welcome back to The Notebooks. If you missed the last, this is where we were.

If you’re coming in fresh, The Notebooks is a piece of long form writing, based on a true story, served in weekly instalments. You can read it yourself or listen to me read it (audio linked above).

Pieces in The Notebooks may have a song-matching, like wine and cheese.

Song-match this piece with: The Coral, Dreaming of You.

Not your quick-release serotonin fix, The Notebooks are in it for the long haul.

Now re-opening The Notebooks to June 2006….

I said this was going to be a High Fidelity mash-up, so let’s talk about fidelity.

Fidelity to the truth? Nah, this is fiction. It’s an exploration of a past, in many ways resembling my own, but it could be anybody’s. Anybody defined (involuntarily) by financial crisis and the new millenium; by weighty expectations, failures and what often (universally?) felt like the wrong choices.

I read Zen and the Art of Archery last week (frankly: don’t bother) and learned from it this one thing: zen aims for the obliteration of the self.

Did you know that? I didn’t. In the context of writing, it is interesting to me.

If zen is the obliteration of the self, literacy may be its highest form of expression.

Hear me out.

Reading, you can obliterate yourself. It’s why I read what other people have to say about things that have happened to them. The more rich and varied perspectives I consume, the more I obliterate myself and my own limitations.

The anodyne is seldom recorded and, weirdly, I have always wanted more of the humdrum. I want to see life in all its quotidian blandness from another set of eyes. An obsession with historical fiction in my young adult phase, as if I could read my way into knowing what it felt like to be on the Mayflower, in Ancient Rome, a starlet in 40s Hollywood or a child in wall-building China. This has always been one of my bugbears when it comes to fantasy or a piece of fiction with cool world-building. Like, let me see more of what’s it’s really like, how it works. Spare me the dramatic narrative, the denouement. I want to spy on the humdrum and marvel at the everyday. I want to see what the post office looks like in Cicero’s Rome or what a casual lunch looked like in Gilgamesh’s Mesopotamia. I want to know what the markets along the Bosphorus smelled like two thousand years ago and what kind of shitters they had on Viking ships.

A prolific Substacker wrote recently about reading (most) books as a waste of time. Don’t want to read books? Think it’s a waste of time? Prefer to stay trapped behind one set of eyes only? Please. Spare me this parochial prisoner’s outlook. You need to zen out, mate. Get off the rat wheel and stop yearning for neat, tidy parcels of information that can be drunk like a smoothie, without moving from your desk, in the most efficient manner possible. Maybe step away from the non-fiction.

What about writing? Is that zen? Surely that’s not obliteration of the self. If anything, it’s the opposite: relentless naval-gazing. This may explain the impression I get that it’s narcissistic for a woman to write about herself (particularly outside the true life context of overcoming some gruelling adversity, learning tough life lessons, etc). As an aside, I have seldom seen men who write about themselves accused of the same narcissism (or, if they are, they are lionised anyway; ref Hemingway).

So, narcissistic. Unimaginative, I grant you, but narcissistic? I am necessarily hemmed in by one body and one perspective on the things that have happened to me. If I write about it, does that make me a narcissist? I would submit that the obliteration of the self in fact lies in writing about one’s self without ego or artifice. Presenting the experience of a life lived as a detached narrative, without any attempt to inflate, alter or enhance.

Simply put: these are all the things I did.

But, like I’ve written before, writing the truth about one’s own life — particularly when that life is a woman’s life — has its challenges. People seem to be much more comfortable with writers of fiction. Maybe fictionalising your life is the zen high-water mark; the real obliteration of the self into an invented self.

Who can say.

I aim for fiction, and sometimes fall short, lacking imagination, constrained to my one body and definitely not zen-like enough.

And, anyway, things can’t ever be recorded with complete fidelity.

—

Robert Macfarlane has written how walking the same piece of land makes it intensely familiar to you. Walking it barefoot makes it even more familiar.

The land I just wrote about in Town and Country, I could walk that, map it with my soles, barefoot, backwards and blindfolded.

I never walked barefoot anywhere in Oxford, except maybe once or twice walking home from a club, blistered and briefly shoeless. Despite its reputation for leafy quads, lush riverbanks and whispering meadows, Oxford isn’t a great place for walking barefoot. Lots of broken glass, smeared take-away remains and a really surprising amount of vomit that I have, at times, bolstered. Like the first night of Fresher’s week, splattering bright pink vodka cranberry all over the side of the Bodleian library, while my new friends looked on with glee.

Wondering how many generations of previous students had vomited just there in that exact same spot lent the occasion a touch of consequence.

Anyway, even though I seldom walked Oxford barefoot, with my French manicured toes, I can still map it.

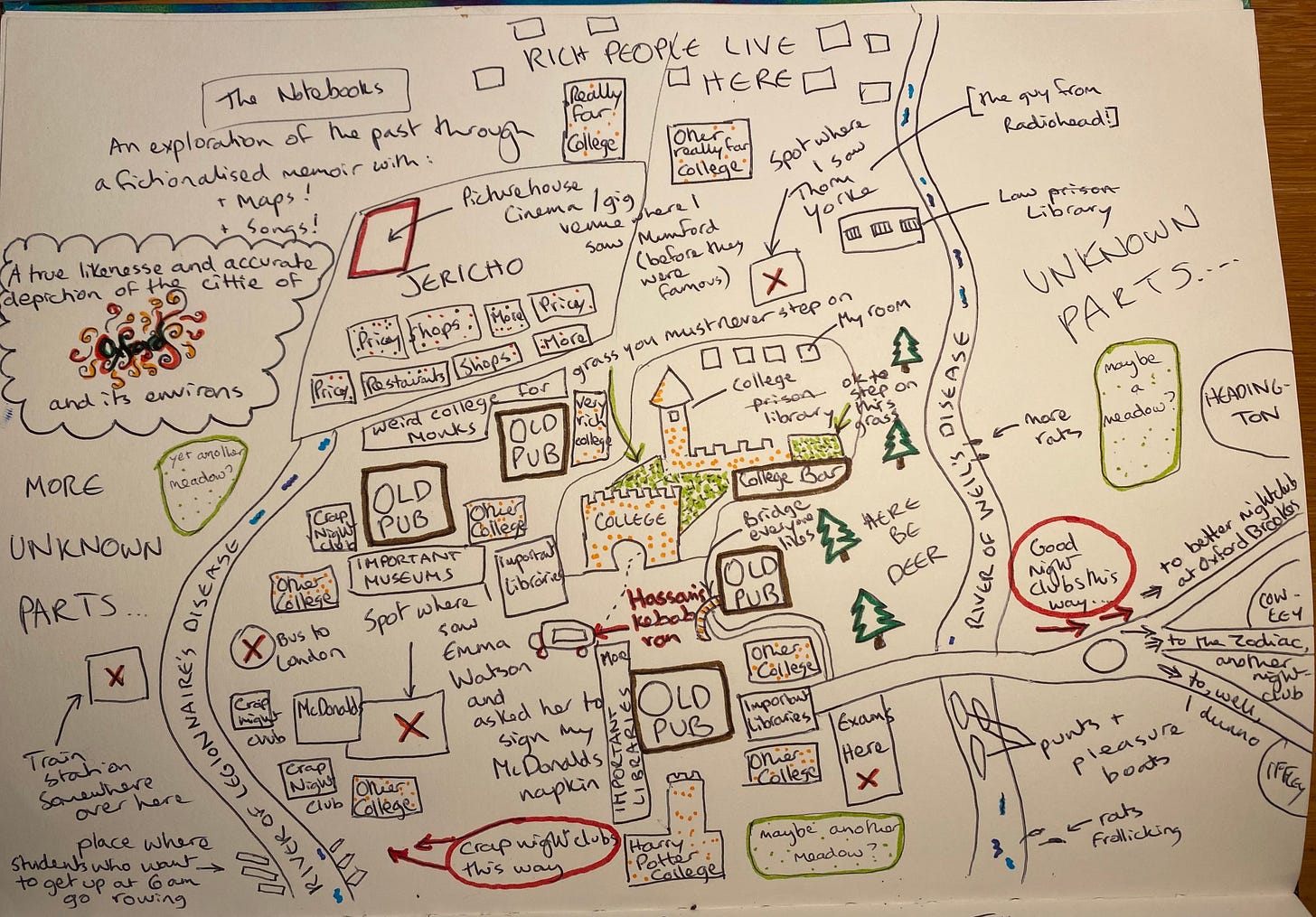

Here it is:

Now, this Oxford has a few (many) gaps. Where’s the covered market? Where’s the High Street? Where are the famous colleges (Magdalen, Balliol)? Where is the pub in which Tolkien dreamed up his maps of Middle Earth or where Clinton didn’t inhale?

Who cares.

This map shows where a hungry student could get a square meal for a fiver (Hassan’s). It indicates clearly that the good nightclubs (the Zodiac and the Pleasuredome at Brookes) were out Cowley way and the shit nightclubs (aptly named Filth and the one above the Sainsbury’s in the old shopping centre) were out Botley way. It includes the prison library. It even shows where a dorky Harry Potter fan asked a 14 year old Emma Watson for her autograph on a McDonalds napkin one wintry night.

Maps are a representation of the world that, by definition, omits things. They don’t show everything; they can’t show everything. A map that showed everything would be as big as the world it mapped and would overlay it perfectly.

This is a map of Oxford circa June 2006, just as I was finishing Finals. It shows the things that were important to me then and omits the things that were unimportant.

I used mind maps a lot when I was studying for Finals. I’ve written before about what Finals entailed, how many essays we had to write. There were nine lever arch folders on the shelf above my desk when I studied for Finals, each about three or four inches thick. Each lever file was filled with single sheets of paper. Each single sheet of paper represented a single case, read in the library, with painstakingly hand-written notes listing out the facts, issues and judgments. The ratio decidendi — the reason for the decision — at the bottom was the summary, the single line summarising it all. The whole case condensed to a single page, then to a single line.

A particularly knotty case could be 250 pages long — or it could be a couple pages. You couldn’t tell looking at the reading list how long each case would be until you got to the top floor of the college library and found the right journal. It was easy then to find the case you wanted because it was the darkly thumbed chunk of that journal — the only momentous judgment reported in October 1874 or whatever. More often than not, the key passages would already be underlined, starred, annotated by one hundred previous generations of college lawyers. That saved a lot of work. I loved the margin notes, always wondered who wrote them, what students before me looked like and thought like. All young men, of course, but that didn’t matter because I was raised on a diet of girls and boys are the same and anything boys can do girls can do and here I was at Oxford, universally male for a thousand years before me so wasn’t it true that we were all the same. I was the same as all those boys before me doodling in the margins of the English Law journals.

I always wondered if some generous philanthropist might take it upon themselves to replace and update the law journals with a brand spanking new set — or worse, just get rid of the hard copies completely and buy all the students a shiny log-in to a database with every case digitised. They would, at a stroke, wipe out the collective accreted work of thousands of Oxford law students over a hundred years.

Those darkly-thumbed mark-ups were like a crucial map through the case; how lost I would have been without them.

That was because we had to read every. single. case. And there could be thirty, forty, sixty cases to read each week. Multiplied by eight weeks of term. By the time Finals rolled around, that equalled about four thick inches of single sheeted case files.

I always found it so easy to read the cases though. The long elegiac verses of judges, kings of law, rolled off the page and hummed through my ears. Some of the facts were wild. Ever heard of R v Brown 1993? If not, your life is about to become measurably richer. And the decisions. Have you ever read a judge’s decision? Unless you’ve ever been a defendant, possibly not. Drawing on the greatest command of words and wit in the English language, the whole thousand-year history of English law from the Domesday book onwards is an exercise in finding the right thing that’s already been said before and saying it in a new way. Trust me, these people are masters of the written word.

In preparation for Finals, the only way to condense those enormous files of cases was a series of mind maps. This case -> another case -> another case. The whole map of Contract law flowered in my head, a series of one word reminders of crucial case to crucial case; the development of what precisely would serve to frustrate a contract; what to vitiate it, make it as if it never existed.

Here’s one of my mind maps from Finals:

Ok, not really. But you know what I mean.

Being a student in Oxford for me was a lot about words, and also about maps. It seems appropriate to write it in words and tell it with a map.

And anyway, writing is mapping too. Writing and maps go so well together. In the same way you can’t make a map with every detail, you can’t write everything that ever happened.

It would be as big as a life.

It’s why we don’t write about every single step of the way. It would be so boring if we did. Can you imagine?

Then I opened the dishwasher and I picked up the colander and hung it up on the rack, then I grabbed a few mugs and lined them up on the shelf. The dishwasher was still pretty full so I couldn’t load it yet. I wanted to finish loading it quickly so I could watch the last episode of Succession. I moved on to the cutlery drawer.

See? Flatlining just writing it.

You can’t cover everything.

Writing is wordsmoke; it creates a hazy shape and may impart a flavour, an aroma of a thing. But it is a simulacrum and will never be the thing itself.

Instead, we “select the data points that are consequential.”1

“Do you think in words?” Joel asked me recently.

“Do I think in words?” I am incredulous at the question. “Does the Pope shit in the woods? Of course I think in words. Have we met?”

He explained that some people think in words, others in pictures. He said he thinks in concepts and associations between concepts. Like a graph.

I can’t even imagine how that would look, let alone how I might try to think in a graph.

I think in words. My whole being is prismatic through words. I think in words, I play in words, I live through words.

There’s a game we play in the car with license plates. In the UK, license plates have a few letters for the area it’s from, a couple of numbers for the year and a few more random letters. The game we play is that you take the last two letters on the plate (the random ones) and have to come up with an 11-letter word that begins with the first and ends in the second. In the UK, everyone apart from the King needs a licence plate, so that’s a lot of random letter combinations to play with.

I think it’s really fun. And it’s not that hard.

Here’s one:

MR. Easy. That becomes “masturbator”.

Here’s another:

RD. Even easier. Reticulated. Reenervated. Rejuvenated. I could go on. There are so many “re” prefix words in the past tense.

Last one:

PC. Trickier. Mostly because of all the “photo” and “phil” plus “ic” words that go way longer than eleven letters. But eventually, I light on paranthetic (how I feel about some discrete stages of my life that can be boxed up separately) or peripatetic (a good descriptor for some of those stages).

I do this pretty quickly. Joel is not as good at it as I am. Words don’t work so well in a mind graph, I guess.

What can I say? Words are my life: they are how I make my living today. They are how I think about my life that’s been and my life to come.

I only got in (talking about Oxford again now) because I can write. Words fly into thoughts, thoughts to sentences, and the sentences string out and loop into one another like the arc of skis through snow.2

I remember realising I was uncommonly good at words when I was about 15. It was a year in which I did no work at all in school if I could possibly help it. This was Irish Transition Year, when you basically get to do whatever you want as you decide what you might like to do with your life. You go on lots of outdoor activity trips and do work experience and ruminate for months over subject choices. This, as a kind of chilled-out balm before the Irish Leaving Certificate (which is like English A-Levels but even more sadistic because you do at least six subjects, instead of three, and often more than six).

Anyway, I skipped school with abandon, faking sick note after sick note. A friend and I camped out at her house, eating her fridge empty and watching Jenny Jones.

Turn my Gothic Queen into a Normal Teen!

It Just Ain’t Right To Wear Clothes That Tight!

At 15, Jenny Jones was the best education I could imagine.

I still did the assigned reading though because, as you may have gathered, I like books. Our assigned reading was Brave New World, a novel I love to this day and still rate above 1984. Where 1984 is an indictment of totalitarian government, Brave New World lampoons class and affluence. Alphas with their skis and their expensive, overwrought leisure equipment; Epsilon Semi-Morons watching TikTok (or the 1920s equivalent).

I genuinely enjoyed it and wrote an essay about how much I enjoyed it.

Because of that essay, I got placed in the top set for English. Writing was easy. The sentences rolled neatly into each other and out came an essay. Another essay. And another, ad infinitum. Here’s me at 15, 16, 17 responding always with an essay on cue, a conditioned response, like Pavlov’s dog, if Pavlov’s dog wrote essays instead of salivated, each one neat as a pin, topped and tailed with references and rejoinders to the question. So easy. How could anyone find this hard?

Then a cover letter, and an essay under exam conditions at the beginning of December 2002 at a college in Oxford. The question was (and I paraphrase):

“Imagine there is a machine called the Experience Machine that you could plug into and program your entire life’s experiences, so you never need feel pain or hunger, only pleasurable pre-selected experiences. Now, write an argument in favour of abolishing the Experience Machine and an argument against its abolition.”

I started my pen off like an inky hare and got halfway through the second page before I suddenly stopped cold. My stomach plummeted. I checked the question again.

Now, spoiler: just to reassure you, I did it right.

But can you spot the obvious trap into which they were trying to lure interviewees who lacked the requisite attention to the *words*? I’ll tell you, in the footnote.3

Anyway, that’s my point. Words were what united us. Words, and our ability to use them. I was primed for a life wherein my chief value would be my ability with words.

Keep doing this, don’t I. Going adrift.

It’s just that, to properly explain July 2006, I need to explain June 2006 too.

Onwards.

Here’s your girl.

She’s sitting at her desk in staircase 21 at the back of college. It’s a Thursday night. Last night of exams. She is about to turn 21. Her toenails are French manicured, ready for a week of partying post-Finals. There are piles of flash cards and neat mind maps. A schedule of Finals pinned to the wall with blue tack, the subdued murmur from the college bar downstairs and the lights of the spired city over a shoulder out the window.

She doesn’t know who she is. She only has a vague idea who she isn’t. She knows she isn’t one of the Cool London Girls with skinny jeans and eating disorders. She isn’t into theatre, or drum and bass. Before Oxford, she’d never even heard of drum and bass. She doesn’t do coke; has never even been offered it. There are lots of classic movies she hasn’t seen until recently: A Clockwork Orange; Pulp Fiction. She’s vaguely preppy, in a confused, provincial and inauthentic way. She has started to experiment with skinny jeans (even though her heart stays with low rise bootcut) and she straightens her hair religiously. There are ragged nests of fried hair under her sink. She likes Krispy Kreme donuts, by the box, as a study aid and has, for months now, chosen a particular seat in the Law Bodleian opposite a cute guy. In fact, just yesterday she managed to talk to him for the first time and get his phone number. His name is Geoff with a G. He’s less cute up close when you talk to him — so many people are, aren’t they — but never mind.

He provisionally agreed to come out and party tomorrow night, post Finals. He told her he has his eye on an internship at JP Morgan next year in the City.

For such a smart girl, she’s really pretty dumb.

How do you make a town like Oxford your own? It belongs so completely to everyone else who has gone before, but of course, they didn’t feel like it belonged to them either.

There’s an iPod in a blue-glowing dock playing Sigur Ros and there’s a landline next to it that is ringing.

I snap back to myself. It’s Thursday 8 June 2006.

Throw down my notes. There’s no point anymore; at this stage, it’s just a comfort thing. Like a soother, a worry stone, Catholic prayer beads. Turn them in your hands and recite: “Quistclose trust …. remoteness of damages …. indirect loss”. The mind maps set off a chain reaction in my head, like a lit fuse, tripping down all the right neural pathways.

It’s Matt. Matt is my friend who also lives in staircase 21. He came dead last in the room ballot so ended up with a crappier room lower down the staircase and without the view. I assume he’s been studying too. It’s what we did. And drank.

“Let’s go to Hassan’s.”

We walked the fifty metres or so to Hassan’s. It’s the nearest kebab van, a haven of warmth and chip fat on Broad Street.

“What will you have darling?”

“Chips and cheese. And hummus.” I can’t make up my mind. “And beans and an egg on top.”

“Barbecue sauce?”

“Yes please.”

Matt is restless. “Should we look in to the champagne and strawberries evening the Law Society is putting on?”

“I can’t drink tonight. Last night. And the Law Society isn’t putting it on. It’s sponsored by Freshfields.”

“I thought it was Fieldfisher?”

“Nah, Fieldfisher did the Fresher’s week drinks in Freud’s.”

“Oh right.”

How do you make it yours? How do you define it? You don’t. You move through it and have the same experiences as everyone else. Probably you have sex with the same person as everyone else and contract the same STIs too.

Or maybe that’s just me. Because my first boyfriend had his merry way with anyone he pleased on the nights out in sticky-soled nightclubs above the big Sainsbury’s in the Westgate shopping centre. Mornings after, when he was nowhere to be found and no one meeting my eye, I would ask innocently “where’s Stan?”

And then you blink and it’s time to go. Like the lights coming on at the end of Indiana Jones but Harrison Ford hasn’t chosen his goblet yet. You haven’t quite managed to grasp the right cup yet; the one that assures you of immortality. Surely it’s somewhere around here but you’re not quite sure where. Maybe it’s in Piers Gaveston but you wouldn’t know because you weren’t cool enough to get a ticket slipped into your pidge.

We walk back to college. He’s eaten his chicken burger and is starting on chips and beans.

“Are you sure you don’t want to get a drink? Just one, calm you down?

“I’m calm. And it’s 10 already, I should get an early night.”

“Ok. Smash it. See you on the other side.”

That reminds me.

“Hey — don’t forget what I said about tomorrow. You promised. No eggs, no ketchup. Flour is fine but don’t get it in my hair.”

He rolled his eyes and grinned.

“Come on, you promised. I want to go out tomorrow night and I don’t want to spend my first free hour post-exams blowdrying my hair. Please Matty, you promised.”

“Jesus, fine, I’ll try not to get it in your hair. You know Tim wants to smash an egg on your head though. I can’t be held responsible for him.”

*All names are made up and any likeness to a real person, dead or alive, is coincidence.

A million points if you spotted that paraphrase? None other than the mighty Wambsgans in Succession. Season 4, Episode 8: The Election.

That’s not my metaphor; a colleague said that to me once. You write like you’re skiing, effortlessly, just flying down a slope. It was lovely and has stayed with me. Thanks Matt S.

An argument “in favour of abolition” is an argument against the Experience Machine; an argument “against abolition” is in favour of the Experience Machine. I got half-way through my “against abolition” argument and realised I had done it right without noticing the major, potential pitfall. Thank fuck.

Awesome post! That Emma Watson appears in Oxford sounds like the most normal thing, lol. Now where is Daniel Radcliffe hiding?

Brilliant. With surprises, and lots of ways to experience and re-experience Oggs too...