008 — Ski season

First love, the oldest ski races in the world — and how it feels to sit at the centre of things, just for a moment.

I grew up on skis. Let me explain.

In upstate New York, the temperature falls below freezing in November and usually doesn’t re-emerge until March.

We had a thermometer outside the kitchen window. Winter mornings, I would check it. Minus 10 or 20 was pretty normal. I remember it being minus 40 sometimes.

On those days, you had to make sure your neck warmer was tucked up under goggles and gloves under jackets at the wrists, so not an inch of skin was exposed. A frost ring would form at your mouth and nose through the layers of fleece.

Snow days, when the plough couldn’t dust the roads fast enough ahead of the school buses, were routine. When it snowed, the snow stayed for months.

It’s cold in winter.

In places like this, with snow and hills, skiing is commonplace. Now, I’m not saying skiing is a cheap and accessible sport. It’s not. Even with snow and hills, skiing remains intransigently a sport for the privileged.

What I am trying to say though is that it is a less rarefied sport in the US than the UK. There’s no snow in the UK, not really, and no hills either, come to think of it. That means that only the very wealthiest can afford regular excursions to the Alps.

But, in the US, when I was a kid, skiing was the kind of thing you might do on weekends or after-school, instead of football (read: soccer) or karate. You might be lucky enough to get lessons and a season pass at the local slope. Or you might beg your mom for twenty bucks for a day’s lift pass and borrow a friend’s skis.

Or you might just find an icy hill and build a booter1 to ride over and over again with your buddies, sharing beers and snowboards.

If you live in a hilly place, covered in snow, you will find ways to play in it.

When you are old enough, if it means that much to you, you will pack up your truck with your dog and your snowboard and head west, to try the real mountains in Colorado, and beyond.

I grew up in this kind of a place.

That’s why skiing for me is like breathing, like walking. I’ve done it for as long as I can remember.

Actually, that’s not strictly true. I can remember things that happened before I learned to ski.

I remember the morning my sister was born. I remember everyone rushing around, I remember being told to go get dressed. I was two. They didn’t know that my mom still dressed me every day. I remember sitting, angry, alone and confused, on the floor in front of my closet not knowing how to get dressed and trying to take something off a hanger but I couldn’t reach it. Then being rushed out the door, still in my pyjamas to go to the hospital to see my mom and the baby. I remember wanting my mom so much and not being able to have her because the baby. I remember someone being angry at me for wanting her.

I remember the scary goat in the back garden. I couldn’t set foot within the circumference of her permitted range of movement. I’m reliably informed we got rid of the goat before my sister was born.

I remember lying in my stroller for a nap in the back garden. Waking mesmerised by the lacework of leaves and light overhead. There was a bird feeder, busy with red cardinals and yellow and black chickadees. I remember sudden pain, falling out the back of the stroller. My mom said I was less than a year old when that happened.

I remember other things too, other pains.

I definitely remember that first day of skiing. I was three. Not wanting to go, the biting cold, the heavy boots, the heavier skis. Trying to lift each leg to sidestep up the red carpet. It was an actual strip of carpet in those days and we had to walk sideways up it. We were so hardcore. Kids today with their motorised “magic carpets” don’t know they’re born, I swear.

The instructors were like aliens, in huge goggles and neck warmers, impossible to see and harder to understand.

“Make a wedge. Wedge, wedge, wedge.”

This was before everyone realised it would be easier to teach kids to make a pizza slice with their skis than a foundational tool of mechanical engineering.

I remember hating it, then not hating it, then gliding and staying upright, then loving it.

I couldn’t get enough.

I was flying!

Flying free and fast.

That feeling has never left me, and shows no signs of leaving still. Skiing is my happy place. Floating up through trees to the top of a mountain, flying down, repeating. The whole mountain bending and arcing beneath me. The smell of snow and pines and wood fires. It is a moving meditation. It is my home. When I ski, I ski with wings.

And I was fast. I am fast. Last winter in Italy, Joel clocked me cruising at 63 mph. It didn’t even feel fast. I’ve definitely gone faster.

The thing is, because it gets so cold in upstate New York, you don’t so much ski snow as compacted ice. I grew up skiing on expansive blue sheets of ice as the accepted norm and I’d liken it to skiing on slippery concrete. If you can ski the ice faces of upstate New York, in minus 40, you are well-seasoned to ski comfortably in most other places (except maybe, you know, Antarctica). As for powder, what is this Elysium?

As a kid, I finished all the levels of ski school by the time I was ten. Parallel turns, slaloms, tuck jumps, 360s — I was done.

Once, I woke up and it was snowing. It wasn’t a snow day though; the ploughs had been through. My mom said to pretend I was sick and stay in bed. She packed my little sister off to school and the two of us went skiing.

If it was winter and I wasn’t in school, odds are I was skiing. I would just lap the same three runs at our tiny local hill over and over again. Faster and faster. Probably hundreds of times a week.

I won first place in the race at the end of ski school. The next fastest kid was awarded fourth place, because there was that much of a margin between my time and hers. I remember her shiny expensive racing helmet and the red, angry face of her dad, struggling to congratulate me. I didn’t wear a helmet or have tight racing trousers. I had a pom pom hat.

Did I want to race? I did, but we were moving to Ireland soon, what was the point of starting racing now.

This is all context.

When I started in Oxford, I’d barely skied in years. After moving to Ireland at 12, I probably only went a handful of times in my teens. Ireland is even flatter and has even less snow than the UK.

Once, age 14, on a visit back to my hometown in the States, I’d gone back to the slope where I’d learned to ski. I knew those runs like my own face, like a face I’d forgotten I had.

Night skiing, under the orange floodlights, I remember hearing a guy whoop behind me, a snowboarder, followed closely by a girl in turquoise, a skier.

It was Luke2 (remember him?), followed by his then-girlfriend, the most popular, blonde and impossibly beautiful girl in my old grade. Watching the two of them, so sure about who they were on territory that should have been mine, was like a hot knife in the gut. I still wanted Luke, still, the same wanting from when I was 11, when he had blue hair and a lunch tray in the cafeteria.

Later that evening, he rode the chairlift up with me, just once. I don’t remember what we said. I remember looking across at him, just once on that one chairlift ride, to see him smiling and joking. I don’t remember a word he said to me, just remember staring in wonder at how close and beautiful his face was. Remember thinking he was so cool.

I caused a lot of drama on that trip by kissing someone else, a someone with a girlfriend. Spoiler: I knew he had a girlfriend. I knew her too, I was staying with her. I just … didn’t care. Because 14 year olds are selfish. Because 14 year old me was selfish. Because I couldn’t have what I really wanted. And what 14 year old relationship is sacred enough not to sabotage, if it will be sabotaged, by another 14 year old?

But I digress.

At Oxford, years later, scrounging for extra-curricular activities, I heard there was a ski club. I heard it was venerable, one of the oldest sporting clubs in the country. And the annual Varsity ski races with Cambridge? Older than the Winter Olympics. I thought maybe I should join and gamely signed up.

Had I ever raced before? Nope, but I was willing to give it a go.

What I hadn’t appreciated is quite how… posh… skiing is in the UK.

Like I said, in the States, it’s a bit more makeshift, a bit more just a backdrop to living in a hilly, snowy place. In the UK, it is the territory of only the most privileged elite; the people in the UK who are good enough to race may not have grown up on the slopes, but they had chalets, multiple trips a season and private instructors since they could walk.

In Oxford, I was on the same ski team as (I shit you not): an Austrian baroness, an Italian countess and an exclusive selection of persons with various levels of title and entitlement.

Remember the person I wrote about with the seventeen iPhones and six iPads or whatever? Guess where I knew them from? Yep, ski club.

Anyway, so I learned how to race (we trained on the dry slope in High Wycombe, which has long since burned down or been burned for the insurance or whatever) and I ended up on the team competing against Cambridge at the Varsity Races in Tignes.

Cambridge beat us that year — they had a girl who grew up in Switzerland, which trumps upstate New York every time, as it turns out — but I was still the fastest girl on the Oxford team. Which pissed off the Italian countess whose fastest time I snatched no end.

Not bad for a gal from upstate New York who grew up skiing the little 500 ft slope a few minutes from her house.

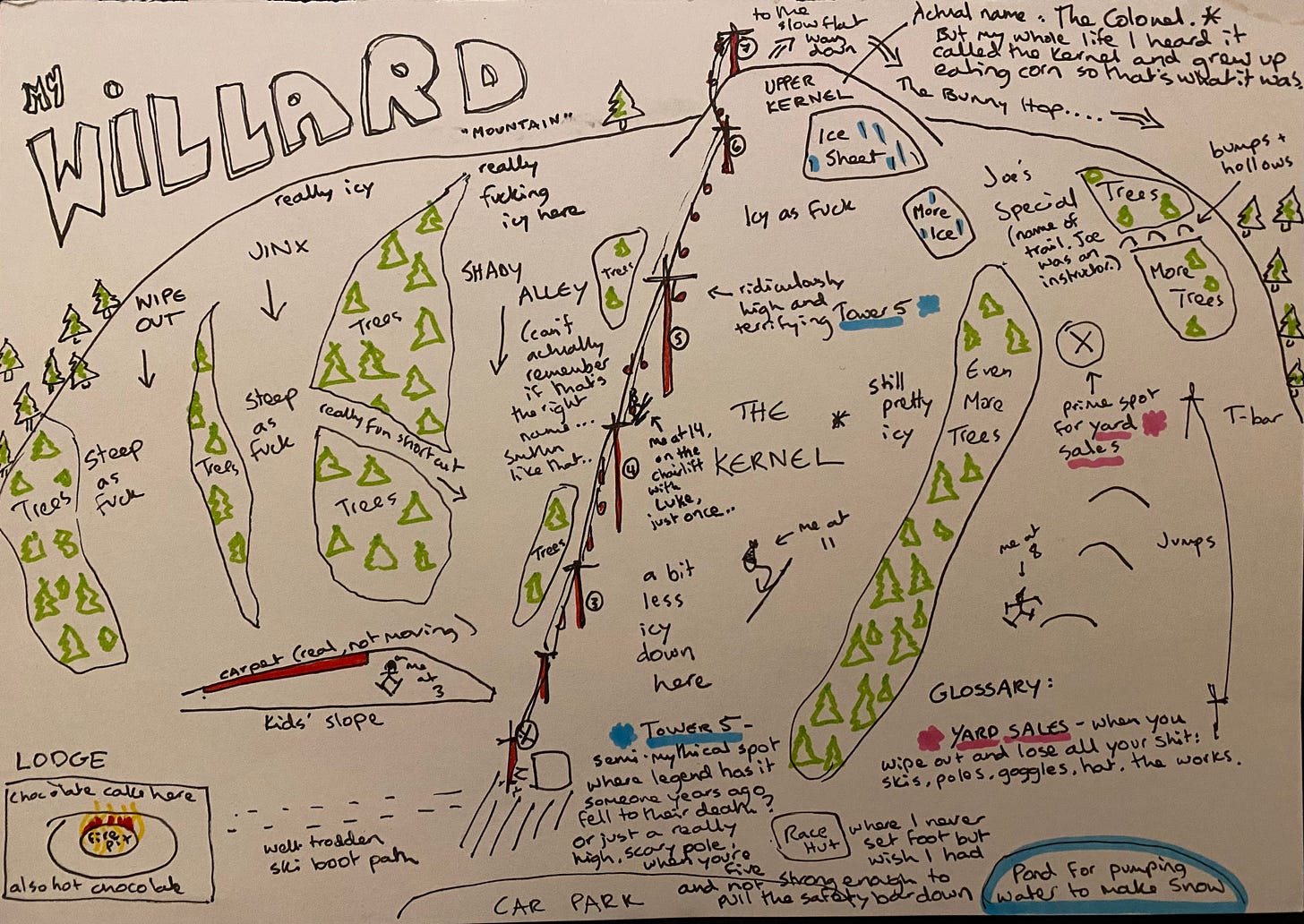

Did you see the map at the top? That’s the spot.

Anyone, even by UK standards, would call it a hill but for locals it goes by the much more elevated name of Willard Mountain and, in my head, it will always be that.

Really though, it’s just a hill in upstate New York, five minutes from the Vermont border. I hesitate to say that area is mountainous, even though technically we are in the Appalachians, one of the oldest mountain ranges in the world. While they might technically be mountains, these rounded-off nubs are really just big hills now, offering only the softest whispers of their vertiginous past.

The hills fold in on each other and enrobe roads, quiet roads, little two-lane affairs that pootle in an unhurried fashion from town to Revolutionary War-era town.

This is the upstate New York where Continental Army troops circulated after losing control of Manhattan; the woods from which guerrilla raids on British supply lines were carried out. In our woods alone, there was the site of an old schoolhouse, a Prohibition-era distillery and countless stone walls that used to mark out fields that have been swallowed up by the woods when settlers abandoned New England’s rocky steeps for acres of flat, loamy goodness in the Midwest. Old Fort Ticonderoga is just upriver. Schuylerville — the home of the Schuyler sisters made famous by Lin Manuel Miranda — is the next town over, fifteen minutes from the house where I spent my childhood. It’s a hotbed of monied Hamilton enthusiasts now, snapping up and renovating the shit out of their 250 year old clapboard homes.

But when I was a kid, it all felt very far from the bright centre of the universe. That was obviously Manhattan, where we’d go on weekends to visit my Grandma by the ocean in Brooklyn and lie with our heads back looking out the dome of the rear windshield to see straight up the ribs of the World Trade Centre. We’d cross the Verrazano to visit cousins in Staten Island and peer down across the air to tankers and cargo ships ploughing the denim of the harbour like toys.

I said to my mom once “we’re so high” and she said there was a famous scene in a movie where someone jumped off that bridge.3 She was somber but I didn’t understand why jumping off a bridge into water would be a bad thing: it sounded like fun. I saw the older boys do it down by the river from our local covered bridge. It was fun. She explained terminal velocity to me. Hitting water from up high is like hitting concrete: bones shatter instantly.

Mountains shatter too. They get pushed up to impossible heights — and eventually stop growing. Tectonic plates shift and the world moves on. New mountains grow elsewhere and old mountains settle, erode and wear down smooth, until their triangles become domes.

In the northern bit of the Appalachians where I grew up, there might be the occasional sharp peak, promontory or steep ravine — but mostly the landscape is soft. Everything is shrouded in dense mixed foliage. At this time of year, in October, it’s on the turn to butter, crimson and burnt orange.

There aren’t many impressive mountains but there is at least one (small) rocky cliff, above a particular cabin in the woods.

I climbed up there barefoot once with another barefoot person, barely remembered.

It was Luke.

It was July 2006.

Remember? Right after Finals, here I was back in my hometown. Right before that train ride.

“You should just move up here and live with me for the next month until I go out to Colorado … It’s quiet and you can just hang out with me and write … ”

We’re sitting on a promontory, a rock face that rises up above the trees behind his cabin and looks out over the green humps of the Adirondacks. We walked up to it through the delicate humid mould of mid-summer and, at times, his hand guides sweaty on my back, even though we both grew up in these same woods, climbed the same trees, walked the same trails.

“What would I write about?”

But that’s not what I mean. I mean, how would I write? How could I be bothered? How would I do anything else when he’s right there, open, available, leaning his face towards me? I look at the veins in his arms and wonder how I would ever do anything but stay here, live in his shack and share his bed forever.

“I don’t know, maybe just about what it’s like living in a shack in the woods... ”

He is pulling me around to face him just by the suggestion in my mind that I could. The sun is hazy and the leaves ripple like strings of green silver dollars. Everything is golden, sunlight on hair and skin; his brows, dark lines. He’s 23 and I am 21 and neither of us have ever been better than that moment.

This is how it feels, right at the centre of things.

He is so beautiful, so strong. I want to draw the lines of his face into my mind forever but it’s too hazy.

I kiss him and wish never to be anywhere else, never to write another word.

—

These woods change so much throughout the year. In spring, they smell like mud and crocuses. In summer, they’re bathed in the green light of elms, ash, maples.

And in winter, the ground is frozen.

People change so much too.

Sometimes, they are soft and fertile; other times, cold and frozen.

—

Song-match this piece with: Future Islands, Back in the tall grass.

Here’s the Notebooks playlist on Spotify:

Jump.

All names invented. Resemblance to any real person is coincidence.

Saturday Night Fever — apparently. I’ve still never seen it.

I started listening to this, and had no idea where it was going. You dip in and out of so many moments across the span of your life, it’s at once dizzying and perfectly emotionally logical. As you kept going, I found I was right there with you. I also grew up in a place with icy hills we called ski slopes because we’d never skied on a real mountain. Boone, North Carolina. You captured the essence of the longing I feel about my childhood in that rural place, and that ache of first love that never seems to leave us.

Wow, a stunning, stunning post! I’ve been waiting a while to read this as it’s a long one, but your beautiful butterfly post this morning was the catalyst for me to make a brew and and fly down those frozen slopes right alongside you. ⛷️ Another awesome read. ♥️