001 — On a train in upstate NY

Truth-telling, self-portraits and a significant train ride.

On a hot afternoon in late July 2006 on an Amtrak train between Albany and Penn Station, I was sitting behind a woman watching a movie on a laptop. She had a blanket over her despite the heat.

After a little while, I became aware that she was masturbating under it. I know. Right there on the train. It was really weird. I had seen men masturbate in public — most notably, the man with a hood over his face who wanked at me and a friend in our school uniforms through the train station railings when we were 15 — but never a woman.

But this was unmistakeable. The blanket was moving up and down and, let’s be clear, I’m pretty familiar with the act in question.

So I got up and went to find the conductor. I found him in the gap between the carriages and told him a woman was masturbating under a blanket in the next car.

His uniform was rumpled and his face sweaty in the hot afternoon. He looked me up and down.

Did you like it? He asked.

Now.

Stick with me, because there’s a point to be made here.

Kathleen Jamie has written — beautifully, pithily — about the Lone Enraptured Male genre of nature writing exemplified by Robert Macfarlane. I would extend it to include travel writing more broadly (see for example Paul Theroux, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Bill Bryson, the list goes on). The Lone Enraptured Male is everywhere.

There aren’t so many Lone Enraptured Females. And that is because, mostly, the Lone Enraptured Female doesn’t exist. She isn’t alone — or if she is, she isn’t enraptured. She is rapt, scared, smiling for her life.

Just like I smiled at that disgusting train conductor.

It might also be because women are more inured to people-pleasing, and people don’t like to be written about. It interferes with their perceptions of themselves, to read about how they might be perceived by others. We don’t want to upset anyone and there are things people don’t want to read about themselves.

Who dropped the ball; who let us down. Who’s into pegging. Who cheated on who and exactly how.

It must be why people who write like this travel a lot. Because it’s easier to write about an encounter with someone you met in a market in Istanbul — a superficial, general encounter — instead of a messy intimate encounter with a person who remains in your life.

So we avoid the messier bits, the bits that might offend.

What then to say about yourself where it necessarily intersects with others?

“What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? / The world would split open.” Muriel Rukeyser

I’m obviously not the first to wrestle with this. In self-portraiture, how to do battle with self-censorship? How do we quantify a life?

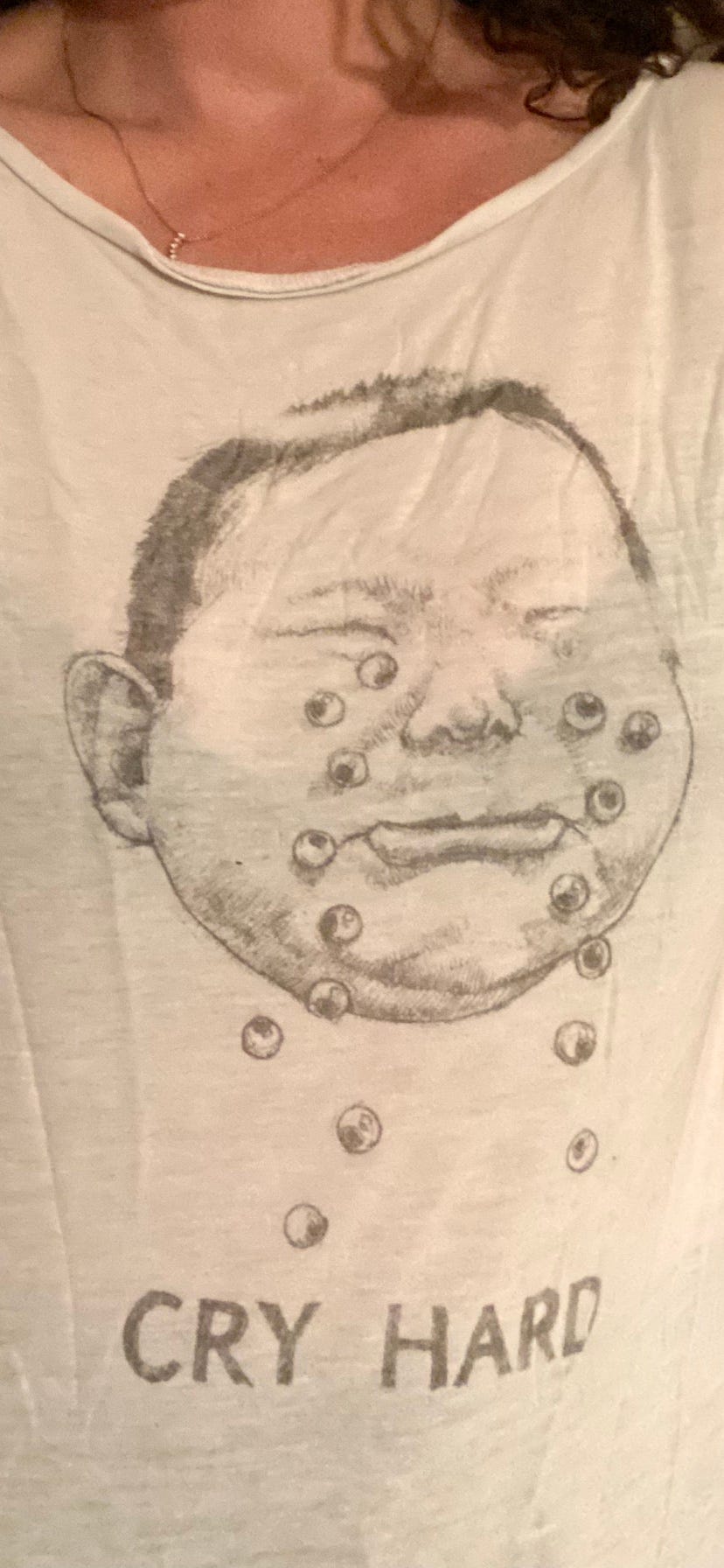

I have 25 T-shirts that I keep carefully folded in a drawer but almost never wear. They carry sentimental weight, like the polyester sporty tee branded with the name of the gym where I did yoga when I lived in Thailand or the June Mountain ‘07/’08 season employee long-sleeved T-shirt that I will sleep in, until one of us falls apart.

But T-shirts can only tell us so much.

Is it how many pairs of shoes I have? I’m not sure. Maybe ten or twelve? Plus four pairs of climbing shoes and a pair of ski boots.

Is it my secret number? It’s 28. I think it’s 28. I hope it’s 28. Maybe it’s 29. I can’t really be sure.

It’s hard to write the kind of history I’m after. Which is no more and no less than the truth of a life, give or take.

“Does it change the way the world feels?” I ask him. “Knowing that 100 trillion neutrinos pass through your body every second, that countless such particles perforate our brains and hearts? Does it change the way you feel about matter - about what matters? Are you surprised we don’t fall through each surface of our world at every touch, push through it with every touch?”

Christopher nods. He thinks.

“At the weekends,” Christopher says, “when I’m out for a walk with my wife, along the cliff tops near here, on a sunny day, I know our bodies are wide-meshed nets, and that the cliffs we’re walking on are nets too, and sometimes it seems, yes, as miraculous as if in our everyday world we suddenly found ourselves walking on water, or air.

And I wonder what it must be like, sometimes, not to know that.”

(From Robert Macfarlane, Underland)

I’m feeling like the cards of life got shuffled and re-dealt and this is a good life. That is as miraculous as walking on water, or air.

But it could have been another way. There were so many improbabilities.

Come with me as I squint into memorial recesses. The old life slides out of focus and the new one sharpens.

It’s early 2010, the middle of the recession.

I’ve just finished a Masters in London. I did it by default because it was the only one that let me defer twice.

I needed to defer twice because I was fannying around California, on trains across Asia and then back to California again.

And I was fannying around there because, as I’ve already explained in an earlier piece about a fancy dinner, I failed to get a first in Finals and, because of that, my postgrad plans changed pretty abruptly. So, after Uni, I sprayed applications around at alternative grad schools and flew as far as I could, to Seattle.

That was November 2006. While my mates were making progress on Their Careers In The City Of London and partying and being bright young things, I was riding a Greyhound bus down the West Coast.

One of my friends in London posted on Facebook: “Saoirse Davison now lives in a house with 5 iPods, 2 MacBooks, 2 iPhones, 1 iPad... and one iPhone4”.

I had no phone and I slept on the floor in Sacramento central bus station, hugging my backpack and waiting for the bus to Reno.

I spent that first winter in Mammoth Lakes, CA, manning the chairlift to get a free ski pass and doing minimum-wage evening jobs — bussing tables in a Mexican and behind the counter in a Chinese take-away — because they afforded the most ski time. I ate cold spring rolls and refried beans. I skied every single day.

I spent the summer in Seattle renovating an arts-and-crafts bungalow in a newly-trendy neighbourhood. Then I flew to Riga and took trains (and eventually buses) to St. Petersburg, Moscow, Irkutsk, Ulaanbatar, Beijing, Pingyao, Xi’an, Chengdu, remote Sichuan, remoter Yunnan, and then down through Laos and Thailand.

I ended up back in California again.

At Burning Man in August 2008, the theme was The American Dream. I covered my $300 ticket by volunteering stints at the central coffee shop. A customer heard I didn’t have a Playa name yet and dubbed me “Cloud”. He said it was for my soft cloud of hair, which I liked because my hair has been my life’s albatross. When I was ten, kids at school used to call me “Bush” — so Cloud was a definite improvement. I drank balché and tried MDMA for the first (and only) time. I rode a bike (this bike), topless with painted tits. I climbed big sculptures high above Black Rock City.

The Man burned and, next month, Lehman imploded. A mate at Barclays Capital back in London got fired in spectacular fashion after losing 250 million in one day. The girl on the front page of the Times — the poster-girl for the Crash in London — carrying her sad little box of possessions out of — somewhere, was it Goldman? — I recognised her. I knew her from from The Bridge, a student nightclub in Oxford. She had been in my year.

When I finally started my twice-deferred Masters course in London in October 2008, days after Lehman, the tutor at the introduction said:

“This is the fullest intake we’ve ever had. There must be something about a financial crisis that just pulls people back in to acadaemia.”

Everyone in the room chuckled. Fresh from California and Burning Man, I remember laughing nervously and thinking: what financial crisis?

So February 2010 found me post-Masters, not gainfully employed, no career, no plan. Working for minimum wage as a sales assistant in the Snow and Rock branch in Covent Garden and living in my boyfriend’s mother’s house in North London on the same street in Muswell Hill as a house engagingly nicknamed The Murder House, for obvious reasons.

That should just about bring you up to speed.

It’s February 2010. I am restless.

London feels like a bad fit, like a dead end. My boyfriend doesn’t understand but I feel…. restless.

California is calling and I want to go back.

But, wait.

Stop.

That is skipping ahead. That is skipping way, way ahead.

We need to go back more.

We need to go all the way back to that hot afternoon in July 2006, a week before I got my Finals results and just after I had fallen in love — for the first time.

—

I feel like there’s a significant detail missing from the story. A detail that could potentially determine it.

What was she watching on her laptop?

There’s a veterans organization called project repat that takes sentimental T-shirts, and makes them into a beautiful fleecey quilts.

I’ve had several made, and if you bring your T-shirts I’ll make one for you