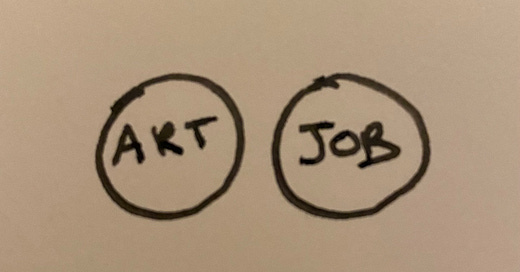

Bread jobs

Cinderella, an awkward encounter with a roofing company and the constraints of necessity.

Upgrade to paid to play voiceover

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Life Litter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.