Wales Part 2: A day in Hay-on-Wye

What mountains and secondhand bookshops have in common, why you shouldn’t use Strava to track your run on an aircraft carrier and all the things we leave behind.

Now, as you may have deduced from Part 1, we just got back from Wales and, as you may also have deduced (nothing gets past you, I know), this is a two-parter.

I am reading a book on the geology of Britain called Hidden Landscapes, which goes very well with climbing mountains, like a fine wine pairing. It got me thinking about landscapes, inner and outer.

I am obsessed by the idea of what we leave behind. And, as you already know, I also wanted to write about a mountain in Wales. How are those two things connected?

Rocks and mountains are the story of crushed shells, dead brachiopods and belemnitic remains. The land outside, whatever we can see, and also what we can’t see, is always the story of what went before. Early sea creatures — trilobites, ammonites — endure for aeons in a quiet sea bed.

What isn’t there is part of the story too. Some plants and animals live in alpine places of great turmoil and erosion — marmots, say, or mountain lions — and so leave no fossil record. It is as if they never existed.

What about us?

I imagine archaeologists of the future finding the triangular shards of beer bottles and viewing them with the same wonder we reserve for arrowheads. A friend, climbing the sea cliffs along the Irish Sea, told me he found an ancient bangle stashed in a handhold. A daring theft and a cunning hiding space? I wonder if the thief slipped on the damp cliff face and so never came back to collect his booty.

Another friend told me about a house in Bath rented by a bunch of students who stapled their used condoms to the kitchen ceiling. Why the kitchen? Drippy additions to the stew add a certain umami depth of flavour? No prizes for guessing what message these students were intending to relay with the detritus they left behind. It’s not Lascaux but, clearly, the impulse to leave behind something (anything) is strong.

The tangible things endure and, in some cases (not used condoms), they call out and hint at tantalising stories we’ll never know.

It’s why I’ve always loved auctions, flea markets and second hand bookshops. The sound of all those stories in my ears like the roar of a conch shell; concentric spirals of conversation diminishing outwards around me. The discernible words to the semi-audible to the steady hum.

In America they call them estate sales, and they are exactly that: the remains of someone’s — a recently deceased someone’s — estate. Essentially, you go into the dead person’s house and have a rummage through their wardrobe, the tin of interesting rocks they once picked up on a beach in Harlech, their souvenir playing cards from Reno, that one weekend. All that is left behind is the detritus of a life lived. The memories attached to those things disperse, like grains of sand in a tide, and the detritus tells only a fragment of the story. Presumably someone has already been through and sanitised the joint, tucking away the dirty pants, chucking out the half-squeezed bottles of lube, burning any revelatory letters and journals. The saleable items are all that remain, to hint at — but reveal nothing of — what really happened that weekend in Reno.

The shoebox of priceless (to us) treasures becomes meaningless, disembodied, divorced from context the moment we die and our inner landscape vanishes.

Last week’s trip to Wales was, to me, a shoebox of priceless treasures. I felt a great pressing need to record it; to anneal it in place and time, like a great lump of granite, so it didn’t disperse.

Often on a train or in a car I’ll want to situate myself in the landscape, so I scroll out on Google Maps, follow along, spotting ridges and escarpments, turning the phone to note the direction of unseen towns. Just so I can situate myself in the land at that moment.

This I did in the car on the way back from Wales.

I told Joel I have a hankering to go to a car boot sale.

He said:

“You’re so adorable. I could never have predicted you would say that.”

“Why not? I’ve just been googling car boot sales near us all morning.”

“So Google could have predicted you’d say that. But not me.”

He’s right. Google knows. My digital footprint will live on to tell the tale that last Sunday morning I googled “car boot near me”. Maps will reveal if I travelled there; my Monzo app what (if anything) I purchased. Even my likes on the new Notes feature of Substack will reveal what I may have been thinking about at various points during the day.

A few years ago there was a great international military secrecy breach when Strava started sharing details of military bases. It turned out U.S. Marines, using Strava to track their runs, were running loops around the deck of their aircraft carrier, which was parked [?] in the Bermuda triangle or Area 51 or some other zone of utmost military secrecy. I think I speak for all of us when I say: duh, and also, LOL.

But here we are again! The residual detritus of a life lived, except these days it’s digital detritus.

It’s why I fear ours will be the age lost to history. Everything about us is electronic. Historians of some distant future will contemplate the end of the twentieth century as the end of our civilization, since that’s where written records seem to fade out. Possibly they will look at the tone and prejudices of many of those books and assume our bigotry led to the war that ended us. If only they could have seen Twitter.

Our phones keep a faithful log of all our movements, and some of our thoughts, our likes, our comments. I imagine we are probably not far off there being an app that you can sign up to and, if you wish, it will create an immutable record of all your posts online and every piece of digital content you ever created after you die. The full record of every scrap of your digital life lived. Your likes, your every movement on Google maps, your heart rate at the exact time you saw the photo of your ex on Insta. Some extroverts would probably volunteer to open theirs up: a public life that anyone could have access to — for research, for creative purposes or maybe just for entertainment.

But, even then, it still wouldn’t track our innermost workings. Apple Health tracks our sleep, our footsteps, our heart rate. But until it can start tracking our brain waves, and logging and capturing our thoughts as effortlessly as it captures our movements through Instagram (and this, Joel assures me, is still some way away), all we have are our pens. And our keyboards.

It’s still the only way to capture all the detritus around the edges that would never otherwise get recorded.

I think as AI makes inroads into traditional spheres of creativity, there will be a premium on this record of authentic human experience. It will become necessary to farm and source experiences — and our thoughts about those experiences — because AI can’t generate original content. It can only recycle and reuse what’s there already. No one else, no other human and certainly no machine, can write what I am thinking or feeling; that is unique to me and, when I go, will die with me. Substack’s value is as a repository of all that authentic humanity. All those writers busily recording their thoughts and feelings and experiences. Much as I wish to be subversive, I fear I am not contraverting tech’s reign but rather feeding it; swelling the mass of source material on which the AI algos of the future will gorge.

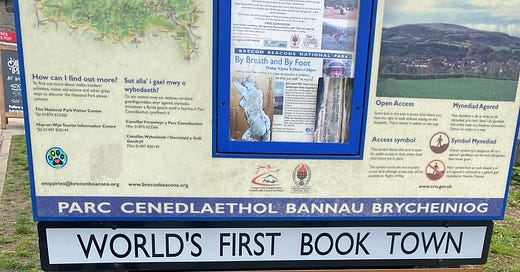

In lieu of any car boot sales, I told Joel I wanted to go to Hay-on-Wye. I’ve wanted to go for years to see what all the fuss was about and, after strapping on my big girl pants for Tryfan, I felt it was time for a quieter pace.

He’s pensive.

“Is it a river?”

“The Wye? Yes. Why yes! It is a river. Why?”

“Every time you say Hay-on-Wye I think of bales of hay stacked on the letter Y.”

This is not at all what I was expecting him to say.

“What?”

“Old fashioned bales, you know, the round ones. And they’re stacked on the letter Y with its arms up like in YMCA with the bales of hay stacked in between the arms.”

I have no suitable response to this, other than to wonder if Dall-E would create me an image of that. Spoiler: it couldn’t, but here is its best attempt:

So we agreed to stop at Hay-On-Wye on the way back from Wales.

Hay-on-Wye is a strange place. I feel I should love it — here are all the things I love! Books, outdoor shops, irreverence! — but I kind of … don’t love it. And I’m not sure WHY (forgive me) this is.

And that makes me uneasy.

Maybe I missed its charms or maybe it was a Sunday or maybe I just couldn’t see past all the London expats pushing thousand-pound strollers. But this felt more like a book cemetery, or possibly more charitably a book museum, rather than a celebration of books. It is a town of books, true, but books as spectacle. As commodity. Leather-bound, and oh-so-Instagrammable. Where were the stories? None of these books hinted at the stories of previous owners, their carefully curated collections. Where were the niche shops for nature writing? For twentieth century Americana? For classics of science fiction? Every bookshop I went in just seemed confused; as if someone had purchased books by the kilo and then thought: Job done. All those old orphan books reaching out, without a story to tell. It made me sad.

In one shop, Joel overheard two women ruminate on whether they stocked Harry Potter.

Now, I’m not trying to be highbrow. I love Harry Potter as much as we all secretly love Harry Potter. In fact, I have the first American edition of the first Harry Potter book because I am (dusts shoulders) about the same age as Harry Potter and read it when it first came out, when I was a kid.

But come on. Harry Potter will be in your local Sainsbury’s. You didn’t need to come to Hay-On-Wye for that.

As we went on, Joel said to me:

“We just passed a place selling Orgasmic Cider.”

“Wow. We should get some.”

“Wait, do you think it was just a misspelling of Organic? Like some farmer meant Organic Cider and accidentally wrote Orgasmic Cider? We’ve got Orgasmic Veg too! Come check it out. This farm is certified orgasmic. All 100% orgasmic.”

“To be fair, it’s easily done. I said it in Science class once. I meant to say “organism” but it came out as “orgasm”. The teacher laughed, and everyone else. It was awful.”

Then, in a cafe a woman behind the counter refused to sell us mushrooms and eggs with our avocado toast, not because she didn’t have any mushrooms or eggs and not because she couldn’t price them as extra items but because she said she needed to “save them because we are running low on stock”.

Now.

Excuse me. But I have worked in many a coffee shop in my time back in my California days and, if I know one thing and one thing only about food retail, it is this first and cardinal rule:

If there are customers standing in front of you that want food that you have and that you would like to sell to paying customers, then you sell it to them. You don’t save it for hypothetical future customers.

Next to me, a woman butts in and asks “excuse me, is that a hedgehog slice?”

Sorry?

“That chocolate slice thing. That’s what we call it in Australia.”

I gave up on Hay then and its Gram-worthy bookshops and its hedgehog slices.

We aimed instead for Offa’s Dyke Path, a trail I read about that follows an earthenwork wall and ditch built by a Saxon king to keep out troublesome Welsh tribes in the eighth century. I will often do this. Read about some very obscure barrow or former nunnery or old Roman road and feel a keen need to go and see it for myself. The land speaks to me with the echo of feet that have passed, and all of their stories. In London, it is a deafening roar, like the sea: bracing but maddening after a time. In the woods of upstate NY, it is a soft shurrur. Even in western Mongolia, where the land and sky stretch impossibly up and night arcs into the whale of the Milky Way leaping from horizon to horizon and the night sky is unpolluted by light and no living creature stirs for a hundred miles, I can hear it.

Lost footfalls like cymbal’s bells, tinkling in my tympanum.

So much for a change of pace. Turns out I just can’t seem to stop walking up hills.

This quickly turned out to be my favourite bit of Hay-on-Wye, as we walked out past the car park to green fields. Soon we were up on an eminence with views across to the far side of the Wye. It was nice to walk on soft grass and mud and not have to look down all the time. It was very, very nice to be able to just trust the ground was still there. The opposite of Tryfan.

I whistled four notes.

“What was that?”

“Just me, whistling tunelessly.”

“It wasn’t tuneless. I recognised it.”

“It’s nothing! It’s just what I whistle when I whistle.”

“That’s why I recognised it. It’s what you always whistle.”

“That’s what I always whistle?”

“Yes. I thought it was a tune you had stuck in your head all the time.”

“No, that’s just my internal whistle. My theme tune. My leitmotif. What was it? I don’t even know.”

“That’s wonderful. You don’t even know what it is.”

I invited him to demonstrate but he was laughing too hard to whistle for several minutes.

Then:

Doo-dee doo doo.

And thus was recorded for all time a vital component of my inner landscape: the pointless whistle.

It started to rain then and we hightailed it back to the car.

But not before formulating vague — but resolute — plans to hike all 179 miles of Offa’s Dyke path.

After Tryfan, it’s good to have a new mountain to climb, and new stories to spin.

Ages since my visit. Lovely village

https://www.lovemoney.com/news/16613/how-to-stage-a-successful-car-boot-sale

So I had to look up car boot sale because I couldn’t figure out what you were trying to buy ha ha here we call it a garage sale. A car boot is something the authorities put on the car to immobilize it if it has too many parking tickets or some other scofflaw.

But your week in Wales sounded adventurous and fun, and the best thing is you’ll have great memories.